Autism Alberta Alliance Update

On November 3, the Autism Alberta Alliance hosted a stakeholder engagement session with participants from all over Alberta. More than 120 key stakeholders registered to attend the event. Despite severe weather and driving conditions, 56 participants were able to make it to Red Deer.

Marie Renaud, MLA

At the end of the session, individuals had an opportunity to share their perspectives on whether the initial objectives of the stakeholder engagement were met. Participants agreed that they had opportunities to:

At the end of the session, individuals had an opportunity to share their perspectives on whether the initial objectives of the stakeholder engagement were met. Participants agreed that they had opportunities to:- Facilitate new connections

- Foster shared awareness of current autism-focused work in Alberta

- Create an initial vision for the Autism Alberta Alliance

- Determine some core objectives for the Autism Alberta Alliance

- Clarify some next steps

An emerging vision statement for the Autism Alberta Alliance also took form:

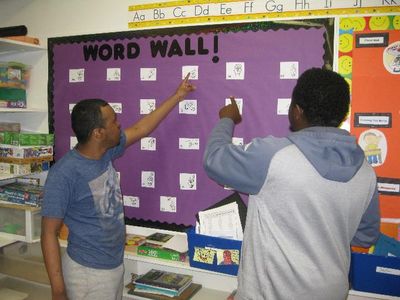

Communicating Through Sign: How a Focus on Communication Reduced Violent Outbursts for a Teenaged Student with ASD

November Update from Autism RMWB

On September 17 we had a bottle drive, and our volunteers did an amazing job helping to collect and sort bottles. The community was very giving, and we raised almost $1400.

On September 17 we had a bottle drive, and our volunteers did an amazing job helping to collect and sort bottles. The community was very giving, and we raised almost $1400. On September 22 & 23 we fundraised by running a hot dog stand. All products and BBQ supplies for the two-day event were provided by The Real Canadian Superstore. It was great to be in the community meeting people, and we collected a lot of signatures on a petition to bring Henson Trust legislation to Alberta.

On September 22 & 23 we fundraised by running a hot dog stand. All products and BBQ supplies for the two-day event were provided by The Real Canadian Superstore. It was great to be in the community meeting people, and we collected a lot of signatures on a petition to bring Henson Trust legislation to Alberta. On October 28 & 29 the Boys and Girls Club of Fort McMurray hosted their Junior Boo carnival and invited us to offer our Sensory Store in their community market. It was two full days of fun for all!

On October 28 & 29 the Boys and Girls Club of Fort McMurray hosted their Junior Boo carnival and invited us to offer our Sensory Store in their community market. It was two full days of fun for all!In our sensory store we are now selling new items like magnetic putty and stress relief Squishy Balls. We also have gift baskets, homemade hot chocolate, cookies, and jars of homemade soup.

- Support 4 Moms Society monthly support meetings

- A Poinsettia Fundraiser on November 20th

- On November 26th, our Christmas Party

- A fundraising opportunity, volunteering for two nights hosting a Christmas party on December 1st & 2nd

- March Bingos

For more event/fundraising details or if you would like more info, please contact us or visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/AutismRMWB/

All the best from Autism Society of the RMWB!

Sincerely,

Board Game Cafe for

Adults with Autism

Where

Centre for Literacy, Suite 100, 9797-45 th Avenue NW, Edmonton T6E 5V8

When

Every second Thursday evening until June from 7:15 to 9:30 pm; next meeting on November 30th

Cost

There is no cost to participate, but pre-registration is required

Call the Centre for Literacy at 780-434-3698 or email info@Centre4Literacy.com

Games

Participants will decide! Games like Dungeons and Dragons, Carcassone or Hive are sure to be in the running.

Companions

Companions and volunteers are most welcome. There is ample room for everyone to relax and mingle.

Organization

This program is being coordinated by Jaime, a Recreation Therapist, who will do her best to make sure everyone has a great time.

Research

This program is being evaluated as part of a research project led by the University of Calgary’s Dr. David Nicholas. All participants will be asked to participate in the research project, but involvement is totally voluntary. Participants do not need to agree to be part of the research project to participate in the Board Games Café. The University of Calgary Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board has approved the research study.

Sponsorship

This program is being co-sponsored by the Centre for Literacy and the Larry and Janet Anderson Philanthropies.

The Centre for Literacy is a friendly site for people using wheelchairs or those who have mobility issues.

Who Will Take Care of Our Kids (When We No Longer Can)? – Part 6

Compounding care challenges is a lack of skilled front line workers. In Alberta, there is no formal certification required to work with individuals with a developmental disability. Many front line workers in agencies are not trained specifically on the unique challenges of ASD, and they may be required to perform additional medical care with no formal medical training. Perhaps even more important is finding the right people. There is a need for individuals who are compassionate, caring and go the extra mile to learn about the interests and needs of the individual with ASD; and who continue to create and build a good quality of life for them. Not all providers, even if they are well-trained, are the best people.

Compounding care challenges is a lack of skilled front line workers. In Alberta, there is no formal certification required to work with individuals with a developmental disability. Many front line workers in agencies are not trained specifically on the unique challenges of ASD, and they may be required to perform additional medical care with no formal medical training. Perhaps even more important is finding the right people. There is a need for individuals who are compassionate, caring and go the extra mile to learn about the interests and needs of the individual with ASD; and who continue to create and build a good quality of life for them. Not all providers, even if they are well-trained, are the best people.– Stakeholder Quote

– Stakeholder Quote

One final observation by the writers of this report, not based on stakeholder interviews, was that there exists a serious problem with fragmented and variable supports. A number of times in this consultation process, agencies or individuals that identified a gap were unaware of other agencies or services that may have ideas to fill it. Examples of this were seen in the creation of a network where adult disability service providers were unaware of agencies already doing this work; the need for a mentorship program when another organization was already doing work in this area; and the creation of a support and care plan template that was already available in another province. Across Canada, within provinces, and even within the same city, there may exist resources and supports that parents and individuals are unaware of. Even if they are aware, the effort to seek out, to meet, to co-ordinate, to do the work, and produce a plan is a lot to ask of aging lifelong caregivers of children and adults with ASD. In addition, this fragmentation causes the re-invention of the wheel of work and added financial strain, both on parents and government; and this is simply a waste of resources.

One final observation by the writers of this report, not based on stakeholder interviews, was that there exists a serious problem with fragmented and variable supports. A number of times in this consultation process, agencies or individuals that identified a gap were unaware of other agencies or services that may have ideas to fill it. Examples of this were seen in the creation of a network where adult disability service providers were unaware of agencies already doing this work; the need for a mentorship program when another organization was already doing work in this area; and the creation of a support and care plan template that was already available in another province. Across Canada, within provinces, and even within the same city, there may exist resources and supports that parents and individuals are unaware of. Even if they are aware, the effort to seek out, to meet, to co-ordinate, to do the work, and produce a plan is a lot to ask of aging lifelong caregivers of children and adults with ASD. In addition, this fragmentation causes the re-invention of the wheel of work and added financial strain, both on parents and government; and this is simply a waste of resources.– Ontario Report

In next month’s issue, we’ll be looking at some of the innovative ideas that exist to fill the gaps in services for adults with autism.

Delivering Jobs with Purpose

We are thrilled to see the progress the Edmonton business Anthony At Your Service has made at creating visible, meaningful and well paid employment for adults with autism and intellectual disabilities. Check out this fantastic TELUS STORYHIVE – Delivering Jobs with Purpose Video or visit their website www.anthonyatyourservice.com to learn about this unique model of employment.

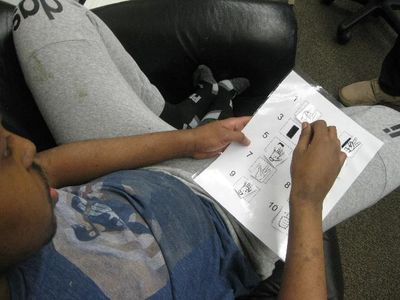

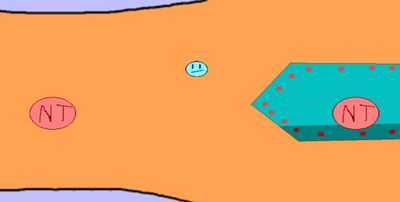

Visual Supports for Autism: A Step by Step Guide

- Create daily/weekly schedules with visual blocks of time

- Show sequential steps in a task such as a bedtime routine or getting dressed

- Demonstrate units of time

- Make a “to-do” list

- Aid communication for those who are less or non-verbal

- Offer choices

Boardmaker (Mayer-Johnson) – This popular software generates Picture Communication Symbols (PCS) and other graphics. The draws are line drawings and not actual photos. Boardmaker does not work for every child because some children do not understand what the line drawings mean.

Boardmaker (Mayer-Johnson) – This popular software generates Picture Communication Symbols (PCS) and other graphics. The draws are line drawings and not actual photos. Boardmaker does not work for every child because some children do not understand what the line drawings mean.- By taking photos with a digital camera

- Cutting out pictures from print media such as magazines or old calendars

- Dollar stores can be a great place to find inexpensive visuals.

We Want to Hear From You!

“Live it to Understand It”: The Experiences of Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

2. “Living and breathing ASD” – A New Form of Motherhood. Mothers often reported that their role vastly exceeded the demands associated with mothering a typically developing child. Mothers described caring for their child with ASD as “a full-time job”, and reported daily feelings of fatigue and weariness. The impact of ASD was described as pervasive, affecting their thoughts, plans, and actions on a daily basis. One mother said, “Every day we always think, ‘what are we going to do for him, what can we find that would help him be better?’”

2. “Living and breathing ASD” – A New Form of Motherhood. Mothers often reported that their role vastly exceeded the demands associated with mothering a typically developing child. Mothers described caring for their child with ASD as “a full-time job”, and reported daily feelings of fatigue and weariness. The impact of ASD was described as pervasive, affecting their thoughts, plans, and actions on a daily basis. One mother said, “Every day we always think, ‘what are we going to do for him, what can we find that would help him be better?’” 6. Redefining Success. The sense of purpose and definition of success reportedly shifted over time for mothers of children with ASD. One mother described the process of redefining maternal and child expectations as “very painful” and “heart-wrenching.” Several mothers reported an immense sense of pride and happiness in events that others would see as normal:

6. Redefining Success. The sense of purpose and definition of success reportedly shifted over time for mothers of children with ASD. One mother described the process of redefining maternal and child expectations as “very painful” and “heart-wrenching.” Several mothers reported an immense sense of pride and happiness in events that others would see as normal:

Nicholas, D. B., Zwaigenbaum, L., Ing, S., MacCulloch, R., Roberts, W., McKeever, P., & McMorris, C. A. (2016). “Live it to understand it”: The experiences of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Qualitative Health Research, 26(7), 921-934. doi:10.1177/1049732315616622

Autism Calgary’s Holiday Party

Sunday, December 10, 2017

11am-2pm

Mount Royal University, Ross Glen Hall

Free parking, see map here

Come join Autism Calgary to celebrate the holiday season in style… with an autism- and sensory-friendly party! Featuring a lunch, face painting, Santa, and holiday music provided by pianist Claire Butler and singers from Silver Stars Musical Revue Society.

*Gluten and dairy-free options available

$5 for adults

FREE for children aged 0-18

FREE for individuals with ASD

For more info, driving and parking maps, and to order tickets online, click here

Autism at the Mall

The Dinner Party Superhero

“You need to use your powers,” I told him. ‘Powers’ is a term we have used since he was a wee one. It’s our way of encouraging him to work through overstimulation – whenever he has managed to behave appropriately, we’ve always told him that he was using his super-powers.

“You need to use your powers,” I told him. ‘Powers’ is a term we have used since he was a wee one. It’s our way of encouraging him to work through overstimulation – whenever he has managed to behave appropriately, we’ve always told him that he was using his super-powers.

As the evening progressed, we made it through dinner with only a few somewhat uncouth conversations at the table. He always has something to say about the way chicken is prepared or how someone looks or smells. In this case, he openly commended himself for not hitting the child beside him; but because he didn’t hit the kid beside him, we considered the awkward discussion a win. He did manage to completely toilet-paper the basement playroom, and his expressively hyperactive behaviour may have wound up our hosts’ golden retriever puppy like a top on speed. But still, nothing was broken, no private spaces were openly invaded, no feelings were hurt from his exceptional honesty, and no other children were bleeding or bruised.

I had never been so proud.

I had never been so proud.